This is an excerpt from “The Mask of Doom: A Nonconformist Rapper's Second Act,” from The New Yorker, Sep. 21, 2009

When Dumile began performing as MF DOOM, he extended hip-hop's obsession with façades. While other MCs fashioned themselves after outlaws, thugs, or drug dealers, Dumile, whose handle is inspired by the Fantastic Four villain Dr. DOOM, called himself “the Supervillain.” When he raps, he often refers to DOOM in the third person. Other MCs are obsessed with machismo; Dumile is obsessed with “Star Trek” and “Logan's Run.”

When Dumile began performing as MF DOOM, he extended hip-hop's obsession with façades. While other MCs fashioned themselves after outlaws, thugs, or drug dealers, Dumile, whose handle is inspired by the Fantastic Four villain Dr. DOOM, called himself “the Supervillain.” When he raps, he often refers to DOOM in the third person. Other MCs are obsessed with machismo; Dumile is obsessed with “Star Trek” and “Logan's Run.”

When I rediscovered Dumile, in his new guise, I was on the cusp of fatherhood and life-partnership, and considering divorce from the music of my youth. My outlook was that of any Golden Age proponent – I was worn down by the petty beefs between rappers, by the murders of Tupac and Biggie, and by the music's assumption of all the trappings of the celebrity culture in which it now existed.

DOOM's music was revancne, and me DOOM persona felt as though it had emerged from the graveyard of rappers murdered by glam-hop. Onstage, DOOM looked the part. He cultivated a dishevelled aspect – ill-fitting white tees or throwback Patrick Ewing jerseys. His paunch gently rebelled against the borders of his shirt. He was visibly balding. His manner suggested a retired B-boy tossing off the trappings of domesticity for one last boisterous romp.

The mask “came out of necessity,” Dumile explained. It was a warm afternoon in Atlanta, where he lives now, and we were sitting in black vinyl chairs in an alley in midtown. Dumile wore a green polo shirt, matching green shorts, a pair of black Air Jordans without socks, and a New York Mets cap. His glasses were missing a lens and sat crooked on his face. He removed the Mets cap and placed it on his knee.

Dumile, who is now thirty-eight, was raised on Long Island, home of several prominent rap groups of the Golden Era – De La Soul, Public Enemy, EPMD, and Leaders of the New School. He started performing during the infancy of hip-hop, when no one had yet realized the potential for big money in a guy talking into a microphone.

“Rhyming wasn't that popular back then, but it was fun,” Dumile told me. “And people would say, 'Oh, you rhyme? Oh, snap, say a rhyme for me! Say another one! Say the one about the girl!' Everybody had a cousin who came out for the summer and could rhyme. And you'd be like, 'Oh, he rhymes? Oh, he rhymes? I gotta meet him.'”

“Ever since third grade, I had a notebook and was putting together words just for fun,” Dumile went on. “I liked different etymologies, different slang that came out in different eras. Different languages. Different dialects. I liked being able to speak to somebody and throw it back and forth, and they can't predict what you're going to say next. But once you say it they're always like, 'Oh, shit!'”

For MF DOOM, Dumile wanted to create a character with a complete backstory, which he would reference through a series of albums. “The story was corning together, and it worked and became popular. And now people wanted to see shows, and I'm like, how do I do that?”

“I wanted to get onstage and orate, without people thinking about the normal things people think about. Like girls being like, 'Oh, he's sexy,' or 'I don't want him, he's ugly,' and then other dudes sizing you up. A visual always brings a first impression. But if there's going to be a first impression I might as well use it to control the story. So why not do something like throw a mask on?”

Or throw the mask on someone else Dumile routinely sends out one of his comrades in the DOOM costume and has him lip-sync the entire show. He sees this as a logical extension of the DOOM idea. Fans who have paid for tickets tend to disagree.

If Dumile had his way, he would take it further. He jokes that he'd like to dart backstage after a performance, take off the mask, and then wade into the crowd – beer in hand – and applaud his own work in conversations with strangers, if the subject of DOOM comes up, Dumile will simply play along, like Peter Parker or Bruce Wayne.

"I'm the writer, I'm the director,” Dumile said. “If I was to go out there without the mask on, they'd be like, 'Who the fuck is this?' I might send a white dude next … I'll send a Chinese nigger. I'll send ten Chinese niggers. I might send the Blue Man Group.”

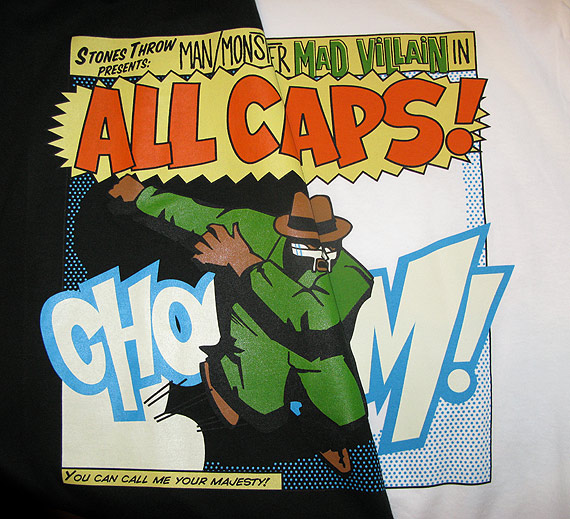

Dumile has released seven albums since Operation: Doomsday. Most of them have been under the name MF DOOM, but he has also used semi-related personas like Viktor Vaughn (inspired by Dr. Doom's real name in Marvel comics) and King Geedorah (the three-headed monster in Godzilla movies). The most highly regarded of his recent albums is Madvillainy (2004), a collaborative effort between Dumile and the Los Angeles-based underground producer Madlib. (The duo dubbed themselves “Madvillain.") The album's production was minimalist, like much of DOOM's solo work. A great hip-hop producer can hear music that spans many genres and assemble it, in bits, into a coherent aesthetic- and Madlib has an ear for samples ready-made to be looped. But the album's singular sound came mostly from DOOM's raspy baritone rendering a sort of nerdcore poetry: “Off pride, tykes, talk wide through scar-meat / Off sides, like how Worf ride with Star-Fleet.”

One Friday in April, I flew out to meet Dumile in Los Angeles, where he was working on his next project, a second collaboration with Madlib. He planned to work the first night, and offered to let me watch the session. But he was running late, and we settled on simply having dinner and starting up on Saturday.

When I called Dumile the next morning, he offered to send his driver and cohort, Five (named for Johnny Five, the robot from “Short Circuit"), to pick me up at the hotel at one o'clock. By two, I hadn't heard anything, so I picked up a book and headed downstairs.

The party had started early. There was a DJ playing MP3s from his laptop a few yards from the pool. Women in bikinis wandered out from the deck into the lobby. Anxious young men in shorts filed in from the entrance. It was exactly what I would have wanted all my Saturdays to be like when I was sixteen. Except that almost everyone was white.

I spotted Five at a table drinking a Bloody Mary. Short and bespectacled, with a long ponytail, he waved happily as I approached. “DOOM didn't give me your number,” he explained. He did not look as though he'd been trying hard to rectify the problem.

We got into his black Chevy Avalanche and drove down Sunset, presumably to see Dumile at work. But there was much to be done before that. We stopped at Amoeba Records to pick up DOOM's new album, Born Like This, since Dumile had not yet heard the finished product. We had to pick up beer, too, a necessity for the transition from Dumile to DOOM. We had to wait for forty-five minutes in front of the house north of downtown where Dumile was staying.

When he emerged, he was carrying some audio equipment and was accompanied by a woman clutching a large bottle of Grey Goose vodka. Dumile packed the equipment in the trunk. The woman handed him the bottle, and he hopped in the back. He picked up the new record and groused about the cover art. “Five, ride around,” he said. “I want to hear how it sounds.”

A great MC is, on one level, a drummer performing a solo. But, more than that, he is a poet, assembling words according to the rules of a particular meter. Dumile offers a darkly humorous take on the life of the DOOM character. There is no single narrative, as much as there are variations on a theme, the most constant being his mask. From the song “Beef Rap” off of his album MM…Food: “He wears a mask just to cover the raw flesh / A rather ugly brother with flows that's gorgeous.”

Hip-hop feeds on the aggression of post-pubescent males. And Dumile draws on the aggression of a particular type of male who came of age in a particular era. When he claims to “eat rappers like part of a complete breakfast,” when he challenges other MCs to battle for Atari cartridges, when he yells “Zoinks!” mid-rhyme, he's signalling those who grew up with, Saturday-morning cartoons and “The Dukes of Hazzard.” For his listeners, his references – “Good Times,” popping wheelies, karate classes – evoke lost innocence, even when the topic is grim. On “Hey!,” DOOM delivers a couplet about some old neighborhood friends, now incarcerated, over a sample from the theme song to “Scooby-Doo”:

To all my brothers who is doing unsettling bids / You could have got away if it was not for them meddling kids.

“When I do it, I feel like I'm thirteen again,” Dumile told me. “I remember, when we were that age, everybody was nice, and everybody was getting nicer. That same well of energy we were drawing from then, I go to there …. To me it feels like that time was richer, every second was really five minutes. Being older now, grown, I'm like, what do we really do that's fun? I'm kind of corny when you think about it. What could I rhyme about? Let me see, um, I gotta pay the rent today.”

The rest of our day bore this out. We spent the hours in the manner of teenagers with nowhere to be, and I saw that Dumile's music sends me back to adolescence because he lives-at least while he's creating-as though he were back there, too.

We wound through the hills of Los Angeles with Born Like This blasting at full volume. Hip-hop is music for warriors – or, at least, for those who imagine themselves as such. I'd listened to Born Like This on my iPod during the flight out and come away unmoved. But hearing a song like “Cellz” – with its lengthy jacking of a poem by Charles Bukowski, pounding drums, and high slicing whistles-at high volume changed my mind.

Dumile had said he'd be working by noon; it was now four o'clock. We came off a sharp curve, and he pointed out a large house on a cliff, which the producer Danger Mouse had recently bought. We stopped at a broad opening, high up. You could see the neighborhoods of Mount Washington and Cypress Park, a commuter train line, the skyscrapers of downtown Los Angeles. With the music still pumping, he walked around for a bit, nodding and making small talk with Five.

Then they hopped back in the car, and Five drove to the studio, a cottage behind a friend's house. Dumile opened the trunk and pulled out a heavy bag filled with rhyme books, which he'd FedExed out the night before, and passed it to me. “If I'm gonna let you see my rhyme books, you could at least carry the bag,” he said.

Dumile took some audio equipment inside. Then he reiterated instructions that he'd given me the night before: there was to be no talking while he was work- ing, not from me, from Five, or from him. He fiddled with a two-hundred-and- fifty-gig hard drive until Madlib's instrumentals pounded out from the speakers, filling the room.

He paused to explain his approach. “When I'm doing a DOOM record, I'm arranging it, I'm finding the voices …. All I have to do is listen to it and think, Oh shit, that will be funny. I write down whatever would be funny, and get as many 'whatever would' funnies in a row and find a way to make them all fit. There's a certain science to it. In a relatively small period of time, you want it to be, That's funny, that's funny, that's funny, that's funny. I liken it to comedy standup.”

I opened the bag and began paging through the rhyme books. It was a great honor – an MC sharing his rhyme books is like a magician sharing notes for his tricks. I half expected a column of light to bloom from the pages. But Dumile's books were like his songs – scatterbrained. and disorganized, a series of potentially humorous couplets. The best ones were written over in black ink two or three times. Few were arranged into verses. Despite his edict of silence, he spent most of the evening trading jokes with Five, yelling nonsensical phrases (“Flurk! Flurk! Flurk!”) into my tape recorder, making bets centered on Five's bad Spanish, and drinking beer. By 11 P.M., it was apparent that very little would get done. We walked out around midnight. “Give it a day,” he said, “and see how things sound in the morning.”

This is an excerpt from “The Mask of Doom: A Nonconformist Rapper's Second Act,” from The New Yorker, Sep. 21, 2009