Two guys, their two dozen personalities, and Madvillainy, an instant contender for hip hop album of the year.

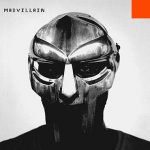

Sitting across from me at the Ramada Inn bar on Ninth and Market, the legendary MC Daniel Dumile — aka Zevlove X, or MF Doom, or King Geedorah, or Victor Vaughn — looks like a complete stranger. Although I’ve almost religiously followed Dumile’s career as he has morphed into different personas — from black radical to postmodern “super villain,” then to alien invader, and on to rogue ladies’ man — I haven’t seen a picture of him in nearly a decade. In every press photo, on each of his album covers, and at his infrequent concerts, Dumile wears a thick metal mask that obscures his face, leaving him austere and enigmatic.

If Dumile leaps into different characters, constantly abandoning one identity for another, veiling any individual essence in favor of anonymity, then Los Angeles MC/producer/DJ Otis Jackson Jr. — best known for his work as Madlib — splits his personality into an ever-expanding cast in order to encompass his various moods, talents, and ideas. Whether jamming with Yesterday’s New Quintet — a jazz “band” made up entirely of Jackson’s aliases — or playing the part of Quasimoto, a helium-voiced hedonist whose primary occupation is smoking herb and “astro traveling,” Jackson occupies a world where he exists amongst his various incarnations, a b-boy Brahma with a blunt dangling from each lip.

While the convergence of these two brands of schizophrenia on the just-released Madvillainy would seem to run the risk of being complete abstract pretense — or just simply overcrowded — the album creates a distinctly unique universe, one that resurrects and remolds 40 years of pop culture into a landscape where identity is fluid and time is out of joint. At times, the album sounds older than the old school, as in the exceptional “Accordion,” featuring an accordion sample that wobbles somewhere beneath MF Doom’s gravelly voice, which recalls the Delta blues as much as it does today’s rappers. But then there are songs like “Shadows of Tomorrow,” which sounds like an apocalyptic dirge made by an alien race.

Although the album is credited to MF Doom and Madlib, Quasimoto and Dumile’s pseudo-suave Victor Vaughn make appearances as they’re needed. Somehow, though, all of the narrative trickery and sonic juxtapositions eloquently create a self-contained empire where all of these various identities can exist in harmony. It isn’t an easy feat, but Dumile and Jackson manage to pull it off by allowing their complementary — though oftentimes contradictory — creative processes to work naturally off one another. The result is the best hip hop album so far this year.

According to Dumile, his mask and reluctance to do press are not mere acts of defiance against the MTV generation. It’s his way of identifying with his audience. “I’m a regular Joe with a potbelly, how all of us are,” he says. “Doom represents everybody. Doom is [someone] that doesn’t win all the time, he’s the one who’s gonna keep coming back.” Throughout our conversation, Dumile refers to Doom in third person. This isn’t an egomaniacal trick, but rather an acknowledgement that the personality generally associated with the man sitting across from me is only another character.

Still, one can’t help but wonder if the guy who created Doom is shielding himself from an industry that he feels betrayed by. Formed in the late ’80s with his brother Sub-Roc, while Dumile was still using the pseudonym Zevlove X, the duo K.M.D. first rose to national prominence on the strength of its 1990 single “Peach Fuzz.” The group presented a jocular take on Afrocentric themes, and although the corresponding album was a success, clouds began to gather shortly afterward.

In 1993, Sub-Roc was killed in a car accident. Devastated by the tragedy, Dumile re-entered the studio to record Black Bastards, an album with much darker hues. With an unrelentingly raw aesthetic, that work dealt with themes such as drug addiction and poverty, and featured an album cover with Little Black Sambo — a longtime symbol of racist bigotry — being lynched. But in the aftermath of the “Cop Killer” controversy, in which Ice-T’s rap-metal song drew the ire of Dan Quayle, K.M.D.’s record label, Elektra, wanted nothing to do with Black Bastards, shelving the album and dropping the act from its roster.

Still reeling from his brother’s death, and watching his career quickly dissolve, Dumile retreated underground — way, way underground — and did not emerge again until 1999’s near-classic Operation Doomsday, on which he was the newly crowned “Super Villain,” i.e., MF Doom. Since then he’s gone on to release two of last year’s most critically acclaimed hip hop records, King Geedorah and Victor Vaughn, as well as a series of instrumental collections titled Special Blends Vol. 1-5.

While Dumile had to claw his way back into the spotlight, his collaborator for Madvillainy has been on a slow ascent for the last several years. Jackson initially came into the national focus in 1999 as the consummate b-boy Madlib, the producer/MC for underground group Lootpack. He next popped up on 2001’s jazz/hip hop classic The Unseen as Quasimoto. To make matters more confusing, Madlib was listed as the producer of, and had guest spots on, that same album; it took months for a disbelieving public to catch wind of the trick. Jackson then went on to form Yesterday’s New Quintet, which contains five different members who all play different instruments and who are all Jackson.

Though he acknowledges that his various personas comprise different aspects of his personality, Jackson quickly points out during a phone interview, “I don’t think so much about it going into it. It just happens.” This spontaneous process lends an unpretentious air to what could otherwise be some very heady concepts. Coupled with an incredible work ethic, it allows Jackson to record a jazz album in a day — he claims that he already has six solo albums for each “member” of Yesterday’s New Quintet — and make multiple instrumental beat tapes a week.

Jackson lives in a world dominated almost exclusively by music, where talk is less than cheap. As we chat, he responds to questions with a “yes” or a “no.” He even stays tight-lipped among his collaborators. About 30 minutes into my conversation with Dumile, the man behind the mask confides, “There were very few words between us — all the words that we’ve had in this interview was as much as me and Madlib had.” As Jackson repeatedly states during our talk: “I like my space.”

Not surprisingly, Jackson’s creative process (which he has dubbed a “freestyle approach”) is in direct opposition to his counterpart’s. Whereas Dumile carefully crafts the parameters of his characters and allows ideas to incubate, Jackson relies on short bursts of inspiration. While Dumile’s characters — and even his career — are long novels, Jackson’s music is a sketch. “Most of my shit is spontaneous,” Jackson says. When I ask him if he’s ever labored over a track for days or weeks, he dryly responds, “Naw, I can’t do that.”

All of this — Jackson’s reclusive nature, Dumile’s past, the dozen or so personalities between them, their conflicting work ethics — would lead one to expect disaster on Madvillainy, but the album is a grand success. It is primal and immediate, beautiful and strange, a tribute to the seemingly disparate genres that inspired it and a rejection of the mentality that says such genres should be kept segregated.

In many ways, Jackson is the Pollock of the hip hop world, slinging chanted nursery rhymes against heaving jazz samples, manically applying swabs of calypso onto boom-bap breaks. There are no choruses on Madvillainy, allowing for 22 songs in 46 minutes, and all the tracks are linked by short interludes that grow increasingly abstract. The album is a trip down the back alleys of our musical consciousness, where high and low art mingle, snippets of childhood recordings interact with Sun Ra and Sonny Rollins.

In this hall of mirrors, where various personas drift in and out of the scene, Dumile’s MF Doom takes center stage, although here we find a more refined portrayal of the character. Doom still has a knack for recycling and warping antiquated clichés — like in “Great Day” when he instructs us to “Put ya’self in your own shoes” — and for engaging in extended vocabulary workouts that employ polysyllabic, inner, and slant rhymes, ample doses of alliteration, and sudden line drops, such as the one in “Meat Grinder”: “Trouble with the script/ Digits double dipped, bubble lipped, subtle lisp/ Midget/ Borderline schizo/ Sorta fine tits though.” Yet there are times when Dumile peers through the dadaist carnival of words and speaks directly, honestly. In “Accordion,” he acknowledges his age, rapping, “Living off borrowed time the clock ticks faster,” before later concluding that it’s “nice to be old.”

Throughout the album, Jackson and Dumile sound both confident and intuitive, and that can be attributed to the aforementioned “freestyle approach,” in which there is little time for either hesitation or self-consciousness, much less the complications and clashes that often arise with this sort collaboration. For Madvillainy, Jackson allowed Dumile to enter his sphere, and the MC responded by forcing all of the voices inside of him to suddenly rush out and into Jackson’s fractured productions. The finished product works so well that at times Dumile sounds as if he could only exist in Jackson’s self-contained world, as if there were some essential, spiritual affinity between the two artists, which, despite their differences, makes a certain kind of sense.

“When I first met Madlib,” Dumile says toward the end of our interview, perhaps alluding to his very first collaborator, Sub-Roc, “it was as though I had met a brother.” After finding a kindred spirit in Jackson and releasing a truly exceptional underground hip hop record, Dumile may still be faceless, but he’s far from anonymous.