Written by Reed Fischer for CMJ, published April 2007.

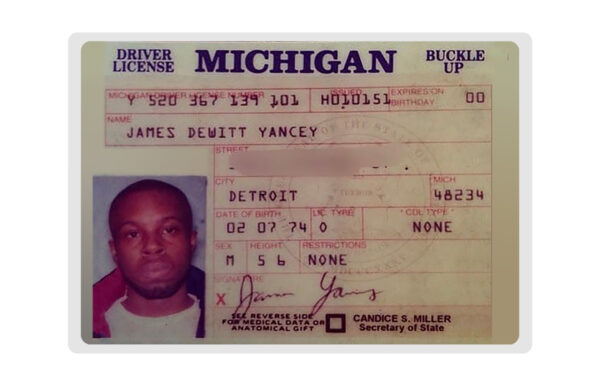

A year after his death, getting to know enigmatic rapper/producer J Dilla hasn’t gotten any easier. It’s well-documented that he was behind a new rap/soul linkage in the Detroit based hip-hop collective, Slum Village. His career-changing production work for A Tribe Called Quest, Busta Rhymes, the Roots, D’Angelo and Common has also turned some heads. We then learned in 2006 that J Dilla, (aka Jay Dee, born James Dewitt Yancey on February 7, 1974), also championed his lesser known musical kin like Frank-N-Dank in Detroit, and worked through great pain, making beats even while confined to a hospital bed. Soon after he died from blood disease TTP in February 2006, devoted fans clogged the OkayPlayer.com message board with speculations about hidden messages in the intricate, sample-suite album, Donuts (Stones Throw).

With the recent reissue of 2003’s Ruff Draft EP, more evidence of his talent as rapper has revealed itself. The 2007 PLUG Awards Artist Of The Year and Record Producer Of The Year rapped about getting slept on critically, but mostly dodged the spotlight. Weight fluctuation from health problems constantly morphed the shape of his face, which he normally hid underneath the brim of a baseball cap. Constant was his impeccably trimmed stubble beard, two determined eyes and a wardrobe of baggy polos and jeans. Appropriately, J Dilla blurred the lines around him just as expertly as he chopped samples. “He could hear something and know exactly how they did it, and make it work for himself,” says Slum Village’s T3.

Raised in a musical household in East Detroit, young James Yancey was the eldest of four, and softspoken due to a stutter he would later overcome. As he grew, he was often in his own world, wearing through pairs upon pairs of headphones and cataloging song titles and sounds in his head. Those sounds morphed into his first beats in the mid- ’80s in basement collaborations with childhood friend Charles “Gator” Moore. By the early ’90s, he debuted on wax with rapper Phat Kat on a project called 1st Down. “He would make the beat right on the spot,” Kat says. “Put flows to tracks in less than 10 minutes flat.” Through a friendship with Detroit producer Amp Fiddler, Dilla’s extensive beat tapes caught the ears of A Tribe Called Quest’s Q-Tip. Jay also hustled his way to Chicago to meet the up-and-comer Common, with whom he would later room. “He dropped two beats for me that I never ended up using for [1997’s] One Day It’ll All Make Sense,” Common explains. “But he came, spent his own money to create some music for me, just so I could have it. From that point on, he was always my guy. That loyalty he showed to me will forever be given back to him and his history and his work.”

Although music did much of Dilla’s talking, there was a flipside, according to his mother, Maureen “Ma Dukes” Yancey. “He was so quiet naturally,” she says. “It would just blow us away to hear him on a record or to see him perform.” His emergence as a rapper began on Slum Village’s first two albums and his 2001 solo debut, Welcome 2 Detroit (BBE). In all cases, his deep delivery added a commanding presence, weaving in and out of the cuts better than scads of more popular performers. It wasn’t until 2003’s Ruff Draft, a vinyl-only EP released overseas, that J Dilla’s flipside was revealed to its full extent.

Tumult led up to Ruff Draft’s creation. His mounting health problems left him weak and even wheelchair-bound at times, and a major-label deal went sour. The highly anticipated breakthrough solo album he had created for MCA, featuring production from fellow first-tier players including Kanye West and Hi-Tek, got shelved, and it remains unreleased. “That was him rapping over everyone else’s beats,” Stones Throw label founder Peanut Butter Wolf says. “He didn’t make one beat on that album. He wanted to flip the whole thing to show that he’s an artist as well as a behind-the-scenes guy.”

What came instead was a fireball. Dilla’s well known, soul-infused Pay Jay productions, like Common’s “The Light” and Pharcyde’s “Runnin’,” took a backseat to the raw power of techno-styled synths and reverb-heavy guitar on Ruff Draft. Wolf, who put out an expanded reissue on March 20, describes parts of the album as “’80s industrial-goth stuff.” Despite Dilla’s rep for dodging credit on some of his biggest projects (Janet Jackson and 2Pac, among them), he is all self-promotion on “The $.” “I’m thinking of a masterplan/I’m blingin’ with the cash in hand/I got a motherfuckin’ right to shine/I paid my dues, I earned this cake I abuse/I burn this paper the way I chose/Gotta handle my b.i., and I do.” Then again, he was showing this side to a small segment of his audience, as if he were trying it on for size. Dilla was idolized, imitated and surpassed in popularity by producers-turned-artists Kanye and Pharrell, but the ever-active Pete Rock was J Dilla’s main inspiration. “He wasn’t about trying to polish up any corners or commercialize [Ruff Draft],” Mrs. Yancey says. “It was just there, raw. It’s just beautiful.”

By the time he released the already legendary Donuts, J Dilla had fundamentally changed. He had matched wits with Madlib on their 2003 Jaylib album, Champion Sound (Stones Throw). Soon after, after an invite from Common, Dilla moved to Los Angeles, and the two lived together harmoniously with Jay’s studio set-up in their dining room. “For me to be able to wake up some morning and just hear him working on music, even though he did a lot of it in the headphones, it would still be like, ‘Man, this is an artist’s dream come true,’” Common says. The place was spic-and-span, which would come as no surprise to his mother, who says Dilla was “a neat freak and couldn’t stand for a piece of dust to fly, much less get it on him.”

When illness hit her son full-on in 2005, and he began a lengthy hospital stay, Mrs. Yancey left her family behind in Detroit to stay by his side. “To keep him out of depression was one of the reasons I started taking the equipment from the house to the hospital, so that he could work,” she says. “That’s where he did Donuts.” It was released on his 32nd birthday, just three days before he passed away. The cover photo, taken from a still from label-mate MED’s “Push” video, shows him smiling under his customary D cap (for Detroit). The title alludes to his sweet tooth (which explains the donut-shaped chocolate birthday cake Stones Throw brought for him), and exposed his sense of humor. Wolf remembers, “He would make up joke names for different beat tapes. One of them was The Pizza Man. When he gave me the Donuts one, I told him we should really call the album that.”

Donuts is distinctly Dilla: glitchy drums, bent notes and trademark touches he used throughout his career, including samples of the Beastie Boys’ Ad- Rock and piercing sirens. On top of that, songs like “Don’t Cry,” “Stop!” and “Last Donut Of The Night” featured vocals belting out phrases like, “You’re gonna want me back,” that expressed sadness and regret, but also hope. Devotees picked apart its contents with care and curiosity. Maybe the 31 tracks fueled speculation that he didn’t expect to see age 32? Was inverting the “Donuts (Intro)” and “Donuts (Outro)” tracks a sign of him entering another, better place? So far, the discussions have translated into unprecedented interest and Dilla’s name getting out there further. Stones Throw general manager Eothen “Egon” Alapatt confirms that Donuts is already one of the label’s greatest successes with about 50,000 SoundScan sales. Also in 2006, producer and close associate Karriem Riggins put the finishing touches on another Dilla project that was close to completion, The Shining (BBE). The album, featuring collaborations with Busta Rhymes, Black Thought and Common, was released in the fall.

Dilla’s production work also appears on Phat Kat’s upcoming Carte Blanche (Look), and “So Far To Go” (from The Shining), will be reborn with new lyrics later this year on Common’s Finding Forever. Another Forever track, “Forever Begins,” includes the lines: “It was in the way which he said Dilla was gone/That’s when I knew we’d live forever through song.” Common put it simply when asked if there’ll ever be another like his departed friend. “Nah, there’s no more J Dillas. Just like there’s no more Michael Jordans.”