IN THE STORE

The Third Unheard: Connecticut Hip-Hop, 1979-1983 CD/2LP/Digital

The Third Unheard Instrumentals 2LP/Digital

J.Rocc Vs. Steinski 12-inch/Digital. Megamixes from The Third Unheard

The Third Unheard Vol. 2: Lonnie O, Tooksee & Czar MC 12-inch/Digital. Bonus material from The Third Unheard

The following, written by The Third Unheard's exec producer, Egon, is an excerpt from the liner notes included in The Third Unheard CD and vinyl.

Old school hip hop is the stuff of legend. The New York City gangs. A truce or two. Rocking block parties in The Bronx. Two turntables and a shoddy mixer. Young, musical visionaries taking then-contemporary breaks and beats from any funky source material and flipping those precious seconds into something wholly new. Don’t forget the microphone. DJs rapping, rappers probably wishing they could DJ (how backwards that must sound to today’s rap-reared youth!). It wasn’t long until this revolution was committed to wax, and the Sugar Hill Gang’s debut single spurred on releases by countless others. The famous, the not-so-famous and the downright obscure all found ways to testify on twelve inches of vinyl. New York-based labels like Sugar Hill, Enjoy and Peter Brown’s multitude of imprints recorded a chorus of thousands of voices.

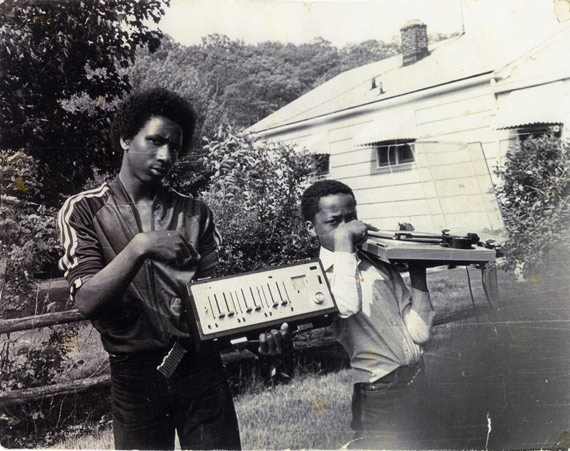

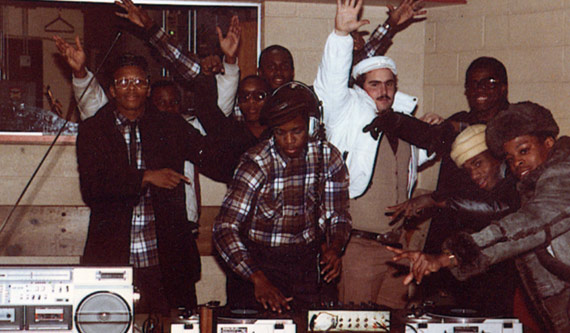

Contributing to this legend are the snapshots of the fledgling stages of a burgeoning scene. Photographers like Jamel Shabazz captured the (re)rebirth of cool on the Big Apple’s streets. Pitchmen like Fab 5 Freddy exported the music and culture to foreign territories (as nearby as a SoHo art gallery). Historians and artists like Phase 2 committed to memory the oral tradition of the scene and designed flyers that, twenty-some years later, serve as colorful reminders of the landmark events where the music’s first heroes honed their craft. Documentarians like the aforementioned Freddy, Henry Chalfant, Tony Silver and Charlie Ahearn created films and books that perpetuated myths, lionized founding figures and influenced music fans the world over.

All this to say – if you desire information on hip hop’s now-legendary roots, you can find some. For instance, the DVD re-release of Style Wars, hardback editions of books such as Yes Yes Y’all and Back in the Days, legitimate compilations of dozens of obscure rap tracks, and the countless bootlegs that have circulated since – in some cases, short months after the first few hundred copies of an indie-rap record were slung from the trunk of some entrepreneur’s car.

However, while old school hip hop aficionados are more than justified to cite New York – and, secondarily, New Jersey – as the nuclei of the old school scene, the third portion of the Northeast’s “Tri-State Area” – Connecticut – lent a helping hand to the movement’s beginning and offered up an ample supply of classic recordings, beginning alongside the release of “Rapper’s Delight” in 1979. Some of the state’s well known records have become part of the wash – attributed to New York groups and like-named New York artists. This may be forgiven. The stylistic variations between the three states’ early takes on rap music are difficult for even the advanced connoisseur to detect. And, given the lack of proper documentation and research relating to recordings originating from urban areas outside of New York City at that time, most old school rap records from the Northeast are lumped into the musical orbit of the five boroughs, for ease of categorization.

This might not surprise a Tri-State denizen, who has learned what living in the looming shadow of New York City means. But for those who relate to the Northeastern United States only as a portion of the map, the close-proximity and interrelatedness of the Tri-State’s cities might be hard to fathom. Obviously, New York is the region’s gravitational-center. Crowded freeways such as I-95 whisk people towards the five boroughs morning through night. Metro-North, Amtrak and Jersey’s PATH trains are filled to the brim throughout the day, shuttling commuters who find their jobs in the City, those who might visit extended family and those who seek the culture and excitement that attracts millions of people from the world over, year after year.

Coastal Connecticut’s cities, specifically those in the southern-most portion of the state, west of New Haven, share a special relationship with New York City. The richest metropolises here – including Greenwich, one of the nation’s wealthiest suburbs, and Westport (not far behind) – have long served as home-base for a large amount of the City’s powerful stockbrokers, executives and celebrities. Further up the coast, cities such as Stamford, Norwalk, Bridgeport and New Haven supply New York with blue collar workers who function as cogs, perpetually in motion within the City’s well-oiled machine.

New York City’s styles and trends exert particular influence on Connecticut’s coastal cities. Derivations of urban slang, dress and musical taste which originate in New York City reach through to New Haven almost immediately. Not surprisingly then, when hip hop reared its head as “the only legitimate youth-driven culture since rock n’ roll,” as Fab 5 Freddy is known to say, it didn’t take long for the seeds to spread throughout Southern Connecticut. And it didn’t take long until those entrepreneurs clever enough to crack the code realized that they would have to record themselves if they were ever to shine like their City-based counterparts. New Jersey spawned a plethora of labels including Sound Makers, Golden Pyramid, Sounds of Jersey, Specific and Chocolate Star. In the early years, Connecticut offered only three imprints: Dynamite Pep, Magic and the appropriately named Tri-State. But these three companies would ultimately go forth to provide the plentiful aural clues that have led to the discovery of unsung rap pioneers – both recorded and otherwise – who might only have existed in the tall tales told by those who witnessed them in action.

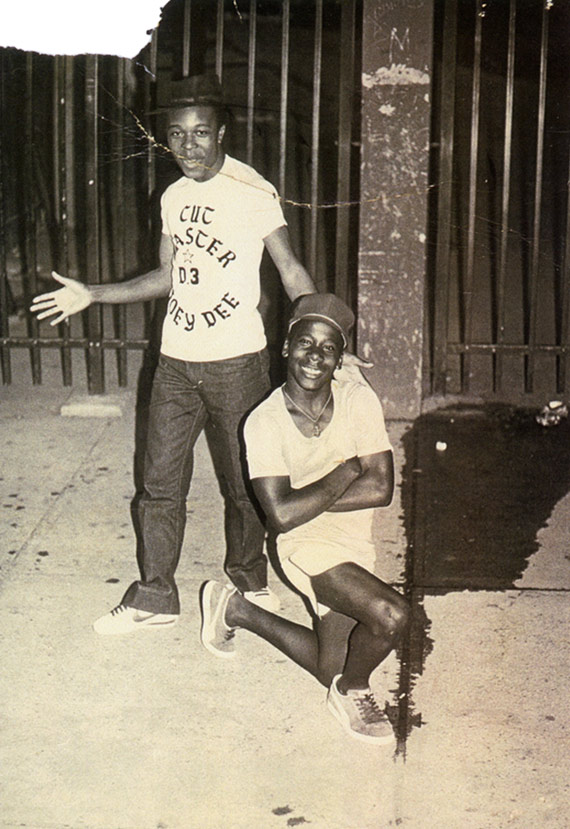

In 1979, Tony Pearson, AKA Mr. Magic, was a twenty-something New Haven-based DJ and owner of the Magic Records store in the small valley town of Ansonia. He had already commandeered the area’s disco and funk scene with the help of protégés Reggie Reg and Gary Bell and friends Leo the Lion, Henry P, Old Man Soul and Funk Machine, Melvin the Music Maker and The Original Cutmaster Joey Dee. His musical trajectory changed, however, when Reggie Reg brought Kurtis Blow’s “Christmas Rapping” to a Christmas Party at a Hudson Street social club.

“He was so excited when he came in with the record. We couldn’t wait to play it ‘cause we knew that cut was going to be the cut,” Mr. Magic remembers. “We put it on, man, and people had never heard it. That’s when I started thinking. I told Reggie and Gary, ‘I’m going to do a rap record and you guys have to be on it with me.’”

He developed a novel concept – to increase his chances of breaking a new musical form in Connecticut, he would write a meandering rap that would start off with a nod to the state (“You know some people say Connecticut can’t rock/But I’m here to make you all hip and hop”) and end with all of Connecticut’s major cities (and some obscure towns such as Ansonia and Meriden) responding “We’re down!” to his roll-call. However this record would never be recorded as planned. The disciplined Mr. Magic had a self-imposed deadline – he wanted to be the first New Englander to release a rap record and, gauging by the gaggle of 12-inches lining the shelves of his record store, he felt nervous that some go-getter would beat him to the punch. Thus, when it became apparent that Reggie Reg and DJ Gary needed time to perfect their sections of the song, Mr. Magic removed their names, transcribed his rap onto a series of cue-cards and contacted a studio in Bridgeport to book a hasty recording session.

As a novice attempting to record rap on a budget, Mr. Magic knew that he could not afford to hire a band to replay the disco breaks that drummer Pumpkin and his friends were churning out for New York labels. And, although he was familiar with the routine of extending breakbeats as a DJ, he was pragmatic as well. “We were going to use (the breakdown from Vaughn Mason’s) ‘Bounce, Rock, Skate…’ I knew I couldn’t keep up that pace as a DJ (for the recording session), ’cause I wasn’t good enough to do that. I wanted the parts to be precise,” Mr. Magic recalls. “I’m a thinker. And I started thinking – how am I gonna do this? What am I gonna do? That’s why, when I talked to (the studio’s engineer) on the phone, I asked him if he could do an idea I had. So I took that breakbeat. And I had him record it. And record it. And record it – and splice it together.” Over the resulting edit, Mr. Magic rapped for four minutes and pressed five hundred copies of “Rappin’ With Mr. Magic” as a double-sided seven-inch on Magic Records at Cook, then a pressing plant based in Norwalk.

The record started its slow grow. Of his three test presses, Mr. Magic offered one to the University of New Haven’s radio station and one to Bridgeport-based DJ Tough Tony. He took a handful of commercial copies to Roger Brousso’s one stop in Hamden, and left the rest in the trunk of his ’63 Chevy. Driving to retailers around Connecticut, he visited Carl Graff’s, a record store located in the Bridgeport Mall. Employee Mike Harrison took seventy-five copies on consignment. But they didn’t last long.

“(Mike) said, ‘I’ll see what I can do.’ So he listened to it, and while he was playing it, right then, someone in the store said, ‘What song is that?’ The kid bought it. Another kid bought another one. So he said, ‘I think you got something here.’ ” Mr. Magic continues, “I left the copies at like 2 PM on a Friday. By 4 PM, my phone rang. It was him. He said, ‘I sold fifty of those records, I can’t believe it! Who’s playing that record?’ I said, ‘Only two people are playing that record so far.’ ” The initial press run of the 45 sold out within weeks.

However, rather than repress the 45, Mr. Magic heeded the advice of a Bridgeport promoter who warned him that he might get sued by Brunswick Records for his wholesale theft of Vaughn Mason’s current hit. Why not hire a band to replay the music, as was the norm in New York, the promoter wondered? “I should never have listened to him, that fucking guy,” Mr. Magic now fumes. “I’m thinking to myself, later on in life, what a jerk I was. I had nothing. What the fuck was they gonna get?”

It took two months for Mr. Magic to record the twelve-inch version of “Rappin’ With Mr. Magic” – now over nine minutes long, and eager to please Massachusetts’ major cities – with childhood friends the Positive Choice Band. He pressed three thousand copies of the twelve-inch at Cook, on a blue and silver Magic Records label, singling out Brousso as his distributor. The twelves would prove more difficult to move than the first run of sevens and most languished in Mr. Magic’s usual haunts.

Peter Brown heard the record and offered Mr. Magic a distribution deal through his Heavenly Star imprint, the label now famous for releasing the superb “Death Rap” by Margo’s Kool Out Crew. Mr. Magic agreed, and Brown poorly remastered “Rappin’ With Mr. Magic” from vinyl, claimed producer’s credit, and named himself publisher. Not that Brown would be able to reap any benefits from Mr. Magic’s labor. “The moment I signed, the fucking guy went to jail!” Mr. Magic exclaims. “He didn’t stay there, but he was in there long enough to knock me off of my course.”

Not that it mattered to Mr. Magic. By the end of 1980, he had released his second twelve on Magic (“Magic Life Coast To Coast” – a “live” version of “Rappin’ With Mr. Magic” featuring the Cuzz Band) and was on his way to founding his second imprint. “Magic Records was too confining ’cause of the hatred that people showed,” Mr. Magic complains of his namesake label. “So I had to bamboozle those fucking folks. I had to be smarter than they were. And they weren’t that smart – so I came up with a recognizable name, Tri-State Records.” He had but to find an artist to develop and release.

The Third Unheard in Village Voice

The Third Unheard in New York Times

The Third Unheard in MOJO

The Third Unheard in Waterbury CT Republican