There was a buzz a while ago about a show at the Knitting Factory in Hollywood. “You gotta go,” someone told me, “because this is Gary Wilson’s first show here in twenty years.” I grimaced and pointed out that maybe there was a reason for that. “No, no,” I was told, somewhat sharply, “this guy’s record is amazing. It’s called You Think You Really Know Me, and he recorded it in his parents’ basement in the late ’70s. Apparently he toured the hell out of it, but it went nowhere, so he packed it in. But it’s been changing hands on the record collector circuit for years and years now. I hear Beck’s a big fan. Anyway, they just reissued the album on CD, but it took them months to find this guy so he could sign off on it, I hear, and when they finally did find him, he was working in a porno shop in San Diego.” And for some reason, that was all it took.

Onstage at the Knitting Factory, Wilson was backed by a crack band, the Blind Dates, and played songs that sounded something like the Talking Heads as fronted by a leering, teenybopper version of Tom Jones. Oh, and every few minutes a stagehand would walk out and dump packages of baking flour over his head. Ghostly white and caked in the stuff, Wilson would grab the microphone desperately at peak moments in his songs, and little white puffs would rise around his hands. I was duly impressed. So this is the guy Beck was talking about in “Where It’s At,” when he sang “Passing the dutchie from coast to coast/Like my man Gary Wilson, who rocks the most.”

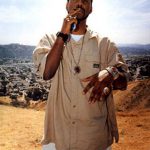

Gary Wilson sat down with me in his San Diego apartment on February 15, 2003 to talk about his career, the development of his style, New Age music, and, uh, pornography. We started out by discussing Forgotten Lovers, his collection of ’70s-era singles and outtakes, released by Motel Records in ’03. A new Wilson album, Mary Had Brown Hair and 12” single, “Newark Valley,” are also due from Stones Throw—stonesthrow.com.

Steven Hanna: Forgotten Lovers disc is really great, and it seems to be getting pretty good press.

Gary Wilson: I guess the official release was January 14, and it’s picking up some momentum. I’ve been watching how it’s doing on the computer. I’ve been stuck in the analog stage for so long, but I got into the digital realm about five months ago, and bought a computer, finally.

You didn’t have a computer before that?

No, even though I used to work for IBM. I finally bought one, though, and so I’m kind of watching, and seeing what’s happening with it. The different radio stations, and what playlists it’s making. It’s beginning to pick up a little bit. It’s good.

Which songs seem to be picking up?

They’re playing different ones. “Forgotten Lovers,” or “When I Spoke Of Love.” People seem to like “Another Galaxy.” That was the first album I made, actually, an instrumental album, and that was a cut from there.

Is it funny to hear that really early stuff?

Well, I always like to say I was still trying to find who I was at the time, but you go through certain things when you’re young until you finally hit a point where you can say “Okay, I’m Gary Wilson, and I am who I am.” It took a while. Well, not a long time, but…

Tell me about those “certain things.” You grew up in Endicott, in upstate New York. How did a nice kid like you get to be making music like this?

I’d been doing demos all my life, since I was in sixth grade. My father was kind of a musician, working at IBM during the day, and being a musician at night. He would play in these lounges, and he had this one gig for, like, 20 years, or 25 years, in this one lounge for like four nights a week. And so he always had tape recording equipment. So I’d been making demos, and taking tapes to places like ESP Records, all these different New York City labels. But I wasn’t getting much action, really. I was playing in different things. I was playing classical music on the side, and I was in a garage band on the side. We had a good band, and we were playing every week.

Was this Dr. Zork (early Wilson band Dr. Zork and the Warts), or…

Well, it was called Lord Fuzz, at the time. Dr. Zork sort of came right after Lord Fuzz. It was the transformation of Lord Fuzz. Lord Fuzz started around seventh, eighth grade, when I was playing organ. The organ I still have out on my porch, actually. And we were, you know…our parents would have to take us to the gigs every week. We were, like, psychedelic. In the ’60s, everything was kind of psychedelic. And we were good.

What sorts of stuff did you play? Your music must have sounded very different back then.

Well, were doing a lot of covers. We used to do, you know, Tommy James and the Shondells, Rolling Stones tunes from Between the Buttons, or Jimi Hendrix stuff. Maybe a couple of things from the Cream. I think the one I used to like was “Live For Today.” I can’t think who did that (the Grass Roots), but that was a cool one.

So you were your basic teenage rock and rollers.

At the time, that’s what you did. But we’d play every week, so our parents would have to take us to the gigs, so that was always fun. You know, when I look back on it, some of those were the best times, with music, for me. Because there was a genuine, real love for the music, and nothing else, no business, nothing else. It was just a pure, real pureness.

What did your parents think of this? You said your dad was a musician, so I assume he understood, but was your mom equally supportive?

I think she was encouraging in her own way about it. My father, what he would do, is he worked at IBM in the daytime, and then he’d go play at night. And he’d be gone, working four or five nights a week in the hotel lounges, and my mother would stay home, and all my friends would gather into the cellar, and, you know, that’s where we would hang out and record and stuff. And my mother would be upstairs, maybe, with a couple of my cousins or something, so I guess she kind of liked the thought of us doing stuff in the basement. She came to my early shows, even when I would do things at my high school and stuff. Not so much the rock and roll part of it, even though she used to take us to all the Lord Fuzz gigs, but she would be more inclined to come to my classical, avant-garde kind of shows. My father was basically the musician, but my mother, by not really stopping me, allowed me to do it, and I think she was happy that I kind of went in my own direction.

How did your dad feel about your going in your own direction? Playing covers of “Purple Haze” is a little different from what he was doing in hotel lounges, I’m guessing.

He was… I’m not going to say he was conservative, but you know… I think he played with Nat King Cole, a couple gigs, and he was kind of a conservative bass player. But he wanted me to see different types of music, I guess. I think my father used to be a little surprised, because I always went into the more experimental end of things. He never said, “Don’t do it, Gary,” because he was a musician himself, but…

You were experimental in your Lord Fuzz shows, or…

I was still playing in a classical thing on the side, at the time. Things were still evolving, and then I became interested in John Cage. I don’t know if you’ve heard any of his music.

I’m familiar. How did you get interested in him? He’s a little far afield from the psychedelic scene.

Well, you see, my father used to wake me up when I was in sixth grade, seventh grade. We had cable in upstate New York, cable to New York City, way way way back in the ’60s, actually, which is funny when I think about it. So we were picking up New York City stations, even upstate. And they would have these, like, cultural programs on, early in the morning, with cutting edge politicians, poets, artists, musicians. So my father would wake me up periodically, to, uh…

What a cool dad.

Yeah, so I said, you know, “Gee, I like that music a little bit.” So I kept going into that kind of music, more and more. My original idol was Dion, of Dion and the Belmonts, and that was in fourth grade. And when the Beatles came out, I said, “Ah, to hell with the Beatles,” but then by sixth grade I went to see the Beatles [at Shea Stadium in ’65—SH], and by seventh grade everybody was into that whole thing. And then, in seventh grade I got kind of into different experimental rock bands. Of course the Mothers of Invention, the Fugs, and different people like that.

I guess that’s kind of the progression of the ’60s, if you think about it.

Yeah, so everything kind of molded together, you know? I had a garage band, and I had a classical band. And then I was into the avant-garde in some ways, and it blended together, and then I had Lord Fuzz by the time tenth grade rolled around. I was probably, let’s see…I was probably 14 when we lost our lead singer and I kind of took over the band.

This was about the time you got into John Cage?

Oh, the year after, maybe. I took over the band, kind of, and then it became more original, more experimental, and I took it into that direction and we started having a kind of modern, experimental rock band by the time I hit ninth or tenth grade. And that’s, kind of…ninth and tenth grade is when I got to meet John Cage, actually, so that all blended into that.

I’d heard you met John Cage when you were a kid. How did that come about?

It was ’cause I was playing in the orchestra, the youth symphony, playing cello and bass. We used to get performances at school of my music. Chamber music, and avant-garde classical music. And my teacher, somehow, maybe she suggested that I write a letter, and get a hold of Cage, ’cause he was out of New York, supposedly.

So you just did.

So I looked him up in the phone book, New York City station, and there he was. John Cage. There was a bunch of Cages, but somehow I got to where he was, and he said, “Well, okay, send me the music, if you want.” And he gave me an address to send it, and about a week or two later he called back, and said he’d like to meet me. And so then my mother, actually, had to take me up there. It was, like I said, tenth grade or something, and my mother took me up to his place.

What year was this?

Oh, it was 1968, or ’67 maybe, and I think it was in Haverstraw, outside of New York City, and we got lost. And we’re there in the middle of the woods, out in the middle of nowhere, so I called John Cage from a phone booth, and he came and picked me up in his car, and drove me to his house. My mother waited in town, I remember. So we drove off in, uh, he had a Thunderbird at the time.

And he just took you to his house?

Yeah, we went to his house, and he hardly had any furniture in his house. He lived in a community that was all cutting-edge poets, architects, artists…and they all lived in this community, and he just had, like, a Buddha doll in one corner, and maybe a hammock stretched across the room in another room. Very little furniture.